The greater sage-grouse has become a national icon for conservation of the sage-steppe ecosystem in western North America. Previously widespread, the species has been extirpated from ~50 percent of its original range, with estimated population declines of 15-90 percent since the 1970s. Loss and degradation of habitat from anthropogenic change is the most important factor leading to isolation, reduction, and extirpation of populations.

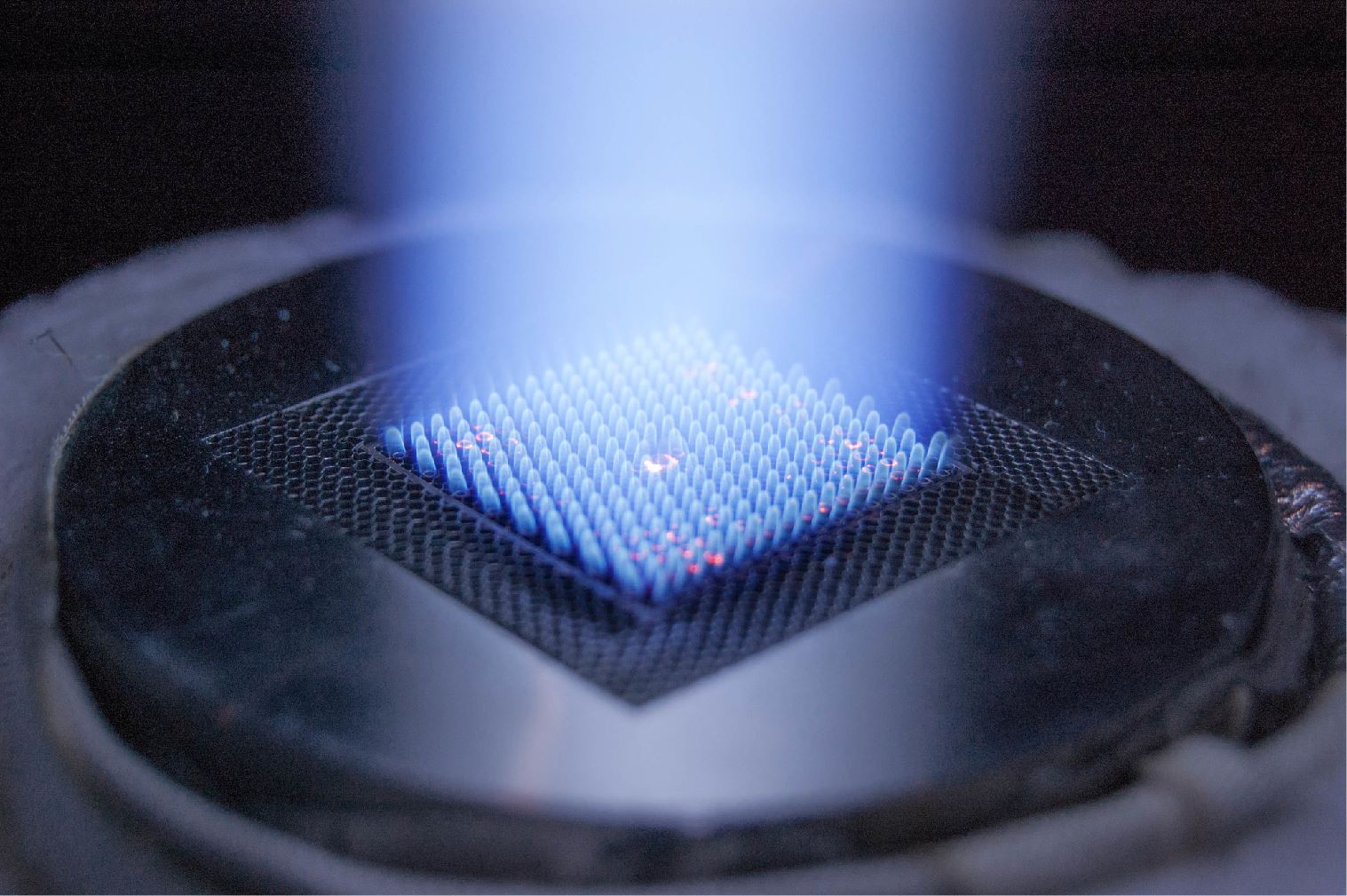

CBNG development in the Powder River Basin is a major component of America’s bid to minimize its dependence on foreign energy sources. Disagreements among government, industry, and environmental groups concerning the adequacy of best management practices to safeguard sage grouse populations have influenced speed and location of development. The crux of the issue lies in understanding whether sage grouse populations are impacted by land use change associated with CBNG development. Specific is the need to know whether birds are avoiding development and whether sage grouse productivity in developed areas is lower than that in undeveloped landscapes.

These and other concerns, such as WNV, were important contributors to the process that led the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to consider protecting sage grouse populations under the Endangered Species Act. A “not warranted” decision from FWS on January 7, 2005, now places implementation of conservation measures squarely on the shoulders of Federal and State agencies and their successful interactions with “sage grouse local working groups.”

The public has placed the onus on government to show leadership in sage grouse conservation because Federal agencies such as the BLM own and manage >60 percent of remaining sagebrush habitats. Federal agencies have called on the scientific community to evaluate whether CBNG development impacts sage grouse populations, and if so, to develop conservation planning tools that empower government to facilitate energy development while providing sound environmental protections.

Results

The following is a summary of results to date for this research:

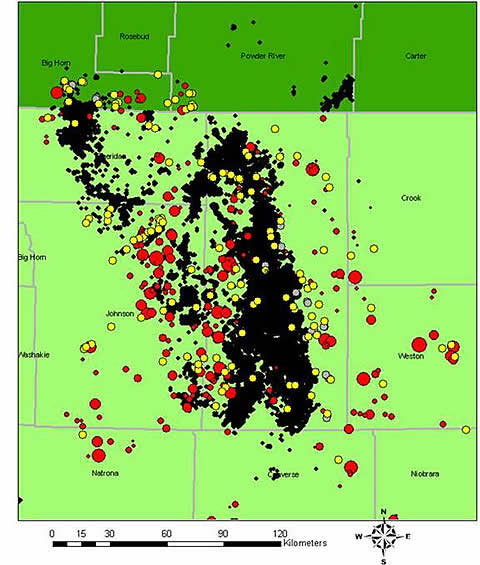

- Male lek (mating arena) count data show the region-wide sage grouse population declined by 84 percent during 1988-2005. In 1990-1995, severe population declines occurred prior to the onset of energy development. After the onset of CBNG development in 1997, the pace of development increased rapidly. During 2000-2005, sage grouse populations in CBNG areas declined by 86 percent, (down 33 percent per year), whereas populations outside CBNG declined by 35 percent (down 8 percent per year). Among lek complexes of known status in 2004-2005, only 34 percent remained active within CBNG fields, compared with 83 percent of leks adjacent or outside CBNG fields. During 2000-2005, leks in CBNG fields had 11-55 percent fewer males per active lek than leks outside CBNG development areas. All known remaining leks with =25 males occurred outside CBNG fields in 2005.

- Findings show that CBNG development is having negative effects on sage grouse populations over and above those of habitat loss caused by wildfire, sagebrush control, or conversion of sagebrush to pasture or cropland. Moreover, the extent of CBNG development explained lek inactivity better than power lines, pre-existing roads, or West Nile virus (WNV) mortality.

- Research findings show a lag effect, with leks predicted to disappear, on average, within 4 years of CBNG development. Intensive monitoring also allowed researchers to estimate the precise timing of lek disappearance relative to CBNG development. Regardless of other stressors, 22 of 24 lek complexes (92 percent) did not go inactive until after CBNG development came into the landscape.

- The current density of CBNG development (80-160 acre spacing) is three to six times greater than the level that sage grouse can tolerate. Leks typically remained active when well spacing was =500 acres (1.3 wells per section), whereas leks typically were lost when spacing exceeded 40 acres (4.2 wells per section).

- After controlling for habitat quality, research shows that sage grouse in winter avoid otherwise suitable habitat that has been developed for CBNG. Sage grouse select for sagebrush flats but avoid rugged terrain and coniferous habitats.

- Avoidance of CBNG areas in winter and the high likelihood of lek loss in spring threaten to severely impact populations along the Montana/Wyoming border, where models classify only 13 percent of area as high quality winter habitat. Options are limited for these populations of birds because they rely on the same landscapes to breed, raise broods, and survive the winter.

- Undeveloped winter habitat is more abundant south and east of the city of Buffalo, WY, than north along the border of Montana. Sagebrush here provides winter habitat for birds that nest as far north as 24 miles, where winter habitat is poor. Unfortunately, the migratory nature of this population means that separate nesting and wintering grounds need to be conserved if this population is to persist.

- WNV mortalities of 2-25 percent per year in radio-marked sage grouse since 2003 show that the disease is a new and permanent stressor to sage grouse populations. Mortality from WNV may have population-level impacts because female survival plays a vital role in population growth. Mortality events from WNV in 8 of 11 states since 2003 support the need to conserve the sage grouse across their remaining range to spread the risk of impacts from disease.

- Research shows that CBNG ponds pose a threat to sage grouse because they provide habitat for mosquitoes that spread WNV. Landscapes with the highest mosquito densities also harbor the highest infection rates in Cx. tarsalis, the species of mosquito that spreads the disease. Larval Cx. tarsalis were produced at similar rates in CBNG and natural sites, and CBNG ponds produced Cx. tarsalis over a longer time period than agricultural irrigation. The sheer number of CBNG ponds and associated mosquito habitat they provide may have implications for human health and safety.

Benefits

Spatially-explicit planning tools, when coupled with knowledge of bird movements and active lek locations, provide a biological basis for decision-makers to formulate an effective conservation strategy for sage grouse. The next step for stakeholders is to formulate a strategy, evaluate alternatives, and initiate implementation.

Summary

Additional research goals are to:

- Analyze vital rate data from radio-marked birds to evaluate whether additional impacts are present that contribute to population declines.

- Validate habitat models using long-term study sites and a new study site where data are collected that were not used to create models.

- Use marked birds to continue this work to realize the full extent of the WNV. (This study was the first to document impacts of West Nile virus on sage-grouse populations.)

- Continue information transfer to stakeholders as a result of this work.