Daniel Boone, James Harrod and George Rogers Clark once explored the wilderness of Kentucky with little more than long rifles and curiosity to find places suitable for new settlements. More than 240 years later, a team of NETL researchers roamed much of the same turf with an array of sophisticated data and equipment to uncover long-abandoned oil and gas wells that could leak methane gas into the atmosphere.

Since the days of Boone, Harrod and Clark, the nation saw big and small industries come and go, mostly powered by oil and natural gas. Much drilling occurred throughout Appalachia to tap needed oil and gas resources. Over the years, many of those wells were abandoned without documentation. Those abandoned wells, known as orphan wells, were drilled long before environmental laws were enacted and many no longer have a responsible operator. Orphan wells can be found all over the country.

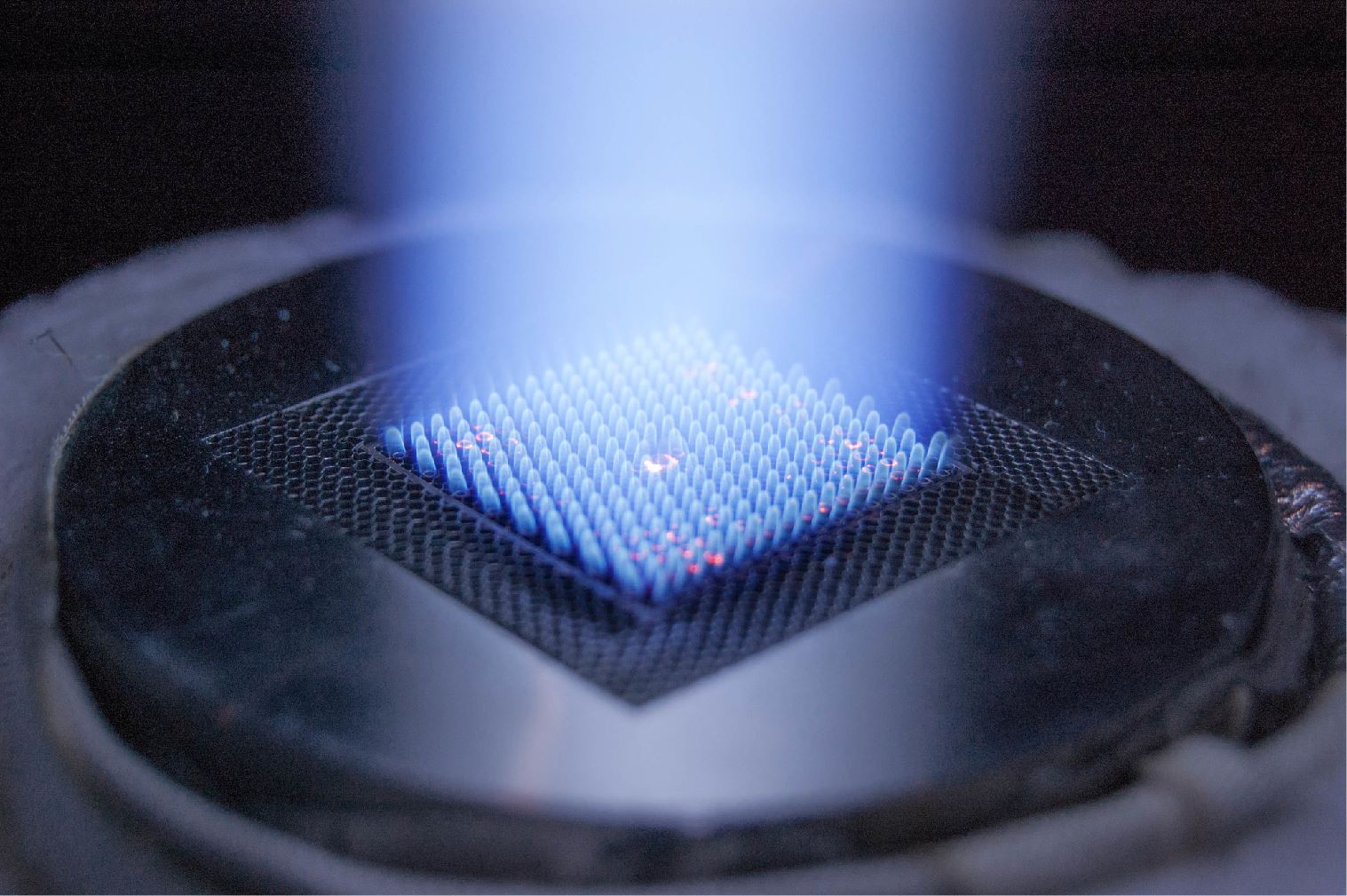

Today, many orphan wells are leaking methane gas, a potent greenhouse gas, and finding and capping them remains a priority as the nation works toward a decarbonized atmosphere. When officials with the Kentucky Geologic Survey (KGS) became aware of NETL’s growing success at finding and documenting orphan wells, they reached out for the Lab’s help.

“The KGS was looking for wells in the Daniel Boone National Forest but did not have the equipment or experience to collect methane emissions measurements,” NETL’s Natalie Pekney, Ph.D., explained. “After they reached out to us, we worked out an informal collaboration to help.”

As a result of that agreement, Pekney took her team to the national forest for the first of three visits.

“Our team met up with the KGS, and we started out by using existing state database locations to find wells,” Pekney said. “Many of the coordinates were inaccurate so the wells were extremely hard to find.”

By the time the NETL team planned its second and third trips to the Daniel Boone National Forest, they were using additional digital resources to map out potential well site locations before trekking through the forest. The team’s array of tools included:

- Well location/production databases — Typically, each state maintains records for oil and gas production activities including well-specific information on status, location, and owner/operators. Searchable national well databases are also maintained by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and by private companies. The data can usually be downloaded for the area of interest in spreadsheet format.

- Topographical maps — USGS maintains a searchable online archive of topographical maps for the entire country. The locations of oil and gas wells are sometimes depicted on the maps along with major infrastructure and elevation data showing the terrain.

- Aerial photography — Air photo coverage is available for most of the U.S. by national and state sources. In forested areas, potential well sites can be spotted by looking for small open areas. Other observable features such as haul roads assist in identifying potential well sites and aiding in navigation planning for field surveys.

- LiDAR — LiDAR uses light in the form of a pulsed laser combined with other data recorded by an airborne system to generate precise, three-dimensional information about surface characteristics. Potential well sites are identifiable as relatively flat rectangular areas with the long side perpendicular to the slope and parallel to the contour of the terrain. An additional benefit of using LiDAR data is that haul roads and trails are visible in much greater detail, allowing for more efficient ground reconnaissance planning.

Pekney said the digital data sources for project areas allow the team to answer key questions associated with orphan well hunting including:

- How many wells are located within the project area?

- What is the spatial distribution of wells within the project area? Are there areas with relatively higher/lower well density?

- How do the location data agree among the sources for each well? Are the locations within 10 m (high confidence), 30m, or greater than 50 m (low confidence)?

- Are there wells that only show up in some of the sources?

- How old are the wells? Is there a predominant vintage?

- What are the physical characteristics of the project area? What type of terrain and topography are typical? Are there any natural or man-made hazards/obstacles that would prevent/permit access to the wells?

- Are there any unnatural disturbances to the land surface?

“Having probable well locations located as accurately as possible before heading out in the field saves time and money by making the final field verification step much more efficient,” she said.

Armed with the array of additional data, the NETL team returned to Kentucky to determine the presence of wells, record high precision coordinates for well locations, and measure methane emissions from the wells that were found.

Two of the 60 wells that were found were leaking measurable quantities of methane.

Pekney said the overall purpose of NETL Daniel Boone National Forest field trips was to demonstrate the effectiveness of layering multiple sources of digital information to facilitate field-based well finding and to increase the sample size of wells from which methane emissions measurements have been collected so that a clearer understanding of emissions distributions for the region could be developed.

Results from the Kentucky work will be included in best practices guidance and shared with state, federal and tribal oil and gas regulatory agencies to aid their efforts to find and remediate orphaned oil and gas wells.

NETL is a U.S. Department of Energy national laboratory that drives innovation and delivers technological solutions for an environmentally sustainable and prosperous energy future. By using its world-class talent and research facilities, NETL is ensuring affordable, abundant, and reliable energy that drives a robust economy and national security, while developing technologies to manage carbon across the full life cycle, enabling environmental sustainability for all Americans.